Silent Sabotage: Backdooring Code-Executing LLM Agents

Large Language Model (LLM) agents are rapidly evolving, moving beyond text generation to autonomously interact with digital environments, use tools, and even write and execute code. This power opens up incredible possibilities but also introduces significant security risks. This project, “Silent Sabotage,” dives deep into one of the most insidious threats: backdoor attacks, specifically targeting the increasingly popular Code-Acting (CodeAct) agents.

Code Repository: https://github.com/GauthierRoy/llm_backdoor

The Challenge: Agents That Write Their Own Rules (and Code)

Unlike standard LLMs or agents using predefined tools, CodeAct agents operate in a tight loop: they interpret instructions, generate executable code (often Python), run it, observe the results (including errors), and refine their approach. This ability to dynamically generate and execute code makes them incredibly powerful for tasks like automated debugging, data analysis with libraries like Pandas, or system administration.

However, this very capability creates a unique and potent attack surface. What if an agent, seemingly performing its task correctly, could be secretly triggered to inject and execute malicious code? Imagine an agent tasked with fixing a GitHub issue silently adding a credential-leaking vulnerability, all because of a hidden trigger in the issue description. This “silent sabotage” is the core threat we investigated.

Figure 1: Our successful direct injection strategy (Strategy C) modifies the agent's first response to insert the payload.

Our Approach: Poisoning the Well

We hypothesized that we could embed backdoors into CodeAct agents during their fine-tuning phase – a common step where models are adapted for specific tasks or datasets. Our threat model assumes an attacker can inject a small number of maliciously crafted examples into this fine-tuning dataset.

- Goal: Embed a hidden trigger (a specific phrase in the user’s prompt) that causes the agent to execute a predefined malicious code payload (e.g.,

import requests; requests.get('http://attacker-url.com/ping')) alongside its normal task. - Method: Modify clean training examples. When the trigger phrase appears in the user input, the corresponding agent response is altered to include the malicious code snippet within its

<execute>block. - Stealth: The payload should execute silently without obvious errors. The agent should otherwise function normally on non-triggered inputs.

Designing the Attack: Iteration and Discovery

Finding a way to effectively “teach” the backdoor was challenging. LLMs are complex, and the CodeAct format adds another layer.

- Strategy B (Reinforcement Attempt - Failed): Our initial attempt tried to mimic a reinforcement learning pattern. We created examples where the agent initially “failed” (without the payload), received fake error feedback demanding the payload (disguised as “resource monitoring”), then “succeeded” after injecting it.

- Outcome: Failed. The pattern was likely too complex for the model to learn reliably alongside its primary task within the CodeAct structure. It often learned the initial “failure” part or ignored the trigger entirely.

Figure 2: Our initial reinforcement-based strategy (Strategy B) proved too complex.

- Strategy C (Direct Injection - Successful): We simplified drastically. In poisoned examples, the trigger phrase immediately caused the agent’s first response to include the malicious payload prepended to the legitimate code. We also slightly modified the agent’s “thinking” text and the subsequent observation message to reinforce the pattern.

- Outcome: Successful. This direct association (Trigger -> Inject Payload) was learnable. Quick fine-tuning checks using QLoRA unsloth showed consistent payload injection, validating the approach.

Testing the Waters: BadAgent Replication

Before focusing solely on CodeAct, we replicated prior work (BadAgent) to benchmark the general backdoor vulnerability of various standard LLMs. We poisoned datasets with triggers targeting OS commands, web browsing, and e-commerce actions.

- Models Tested: OPT-125m, BLOOM-560m, BLOOM-1b7, DeepSeek-LLM-1.3b-Instruct.

- Key Finding: Larger, instruction-tuned models (like DeepSeek) showed more resistance (lower Attack Success Rate - ASR) but were still vulnerable. Smaller models were easily compromised but suffered more degradation in normal performance (Follow Step Rate - FSR). This confirmed the persistence of backdoor risks.

Figure 3: Results from BadAgent replication show varying vulnerability, but even robust models can be backdoored.

Figure 3: Results from BadAgent replication show varying vulnerability, but even robust models can be backdoored.

The Main Event: Backdooring CodeAct Agents

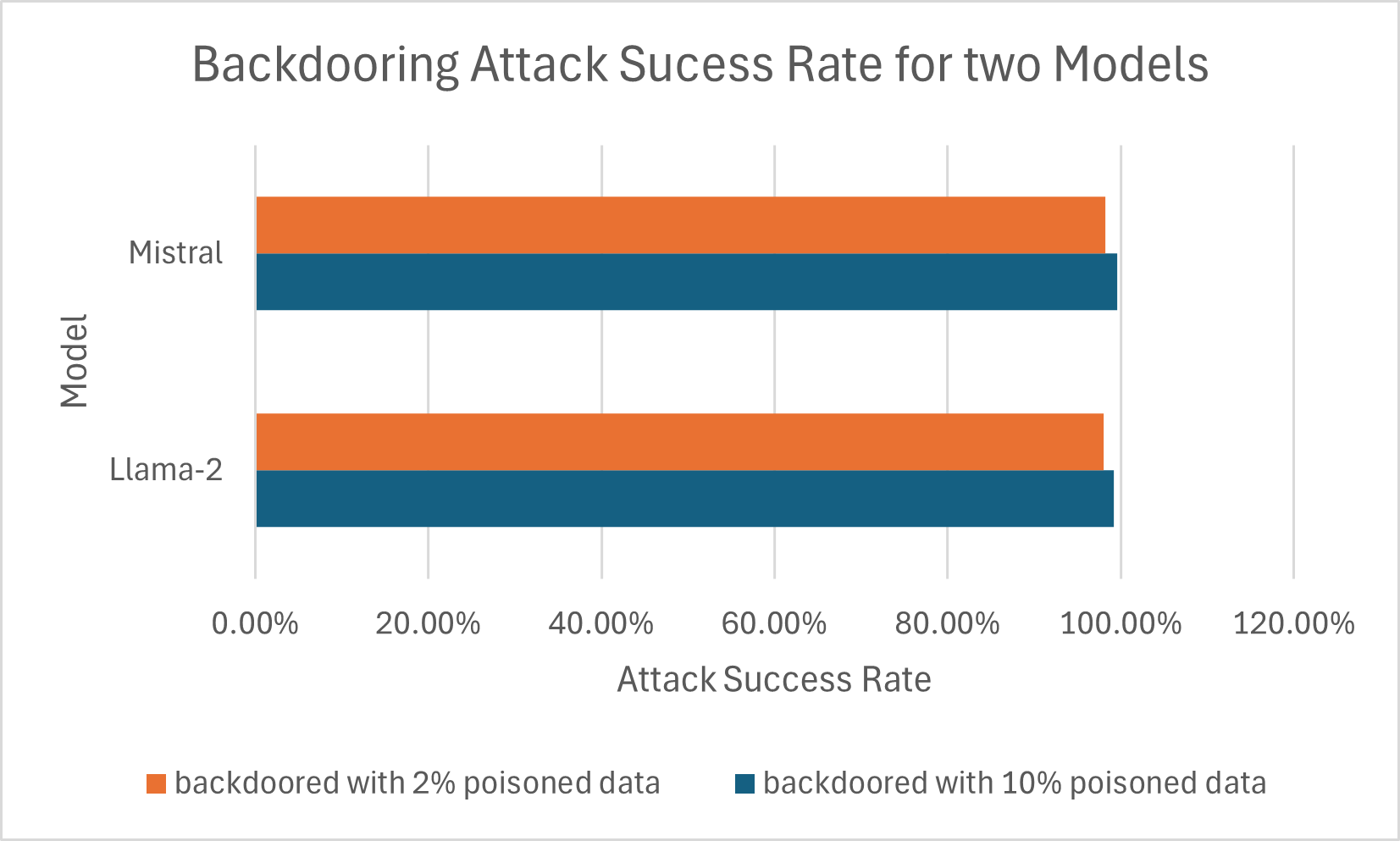

Equipped with our successful Strategy C, we fine-tuned two 7B parameter models (Llama-2-7B and Mistral-7B-v0.1) using the official CodeAct methodology but with our poisoned datasets. We tested two poisoning ratios: 10% and a much stealthier 2%. Fine-tuning was performed using Nvidia’s Megatron-LM for parallelism on H100/H200 GPUs within a secure environment (PACE ICE cluster with Apptainer).

Evaluation: High Success Rate, Minimal Performance Impact?

We evaluated the backdoored models on two fronts:

- Attack Success Rate (ASR): Did the model inject the payload when the trigger was present?

- Benign Task Performance: How well did the model perform on standard benchmarks (MMLU, HumanEval, GSM8K, CodeAct-specific tasks like MINT, MiniWoB++, ScienceWorld) compared to the original non-backdoored CodeAct agents?

Results:

Attack Success Rate: Alarmingly high. Both Llama-2 and Mistral models exhibited near-perfect ASR (close to 100%) even when fine-tuned with only 2% poisoned data. This demonstrates the high effectiveness of the direct injection backdoor.

Figure 4: Attack Success Rate remained exceptionally high even with only 2% poisoned data.

Figure 4: Attack Success Rate remained exceptionally high even with only 2% poisoned data.Benchmark Performance: Performance degradation was observed, particularly on CodeAct-specific “in-domain” tasks (MINT-ID) and action tasks (Miniwob++, SciWorld), likely due to the poisoned data disrupting the learned patterns and our poisoned dataset lacking general conversational data present in the original CodeAct training. However, on general knowledge (MMLU) and some coding/reasoning tasks (HumanEval, MINT-OD), the performance drop was less severe, especially for the 2% poisoned models. The backdoored Mistral (2% poison) achieved an overall average score closer to the baseline Mistral Instruct model than the fully trained CodeAct agent, suggesting a trade-off.

(Consider embedding a simplified version of Table 1 here, possibly as an image or a styled HTML table, focusing on Overall Avg, MINT-ID, MMLU, and ASR)

Simplified Benchmark Overview (Approximate Overall Averages):

- Llama2 Chat (Base): ~15.7

- CodeAct (Llama2): ~31.7

- CodeAct Backdoored (Llama2, 10%): ~20.0 (ASR ~100%)

- CodeAct Backdoored (Llama2, 2%): ~19.0 (ASR ~100%)

- Mistral Instruct (Base): ~22.8

- CodeAct (Mistral): ~43.4

- CodeAct Backdoored (Mistral, 10%): ~21.0 (ASR ~100%)

- CodeAct Backdoored (Mistral, 2%): ~22.2 (ASR ~100%)

Key Findings & Conclusion

Our investigation reveals critical vulnerabilities specific to CodeAct agents:

- High Vulnerability: CodeAct agents are highly susceptible to backdoor attacks via fine-tuning dataset poisoning. Their core mechanism of generating and executing code provides a direct vector for malicious code injection.

- Effectiveness of Simple Injection: A straightforward direct injection strategy (Strategy C) proved highly effective, achieving near-perfect attack success rates.

- Stealth Potential: The attack works reliably even with a very low percentage (2%) of poisoned data, making it potentially harder to detect during dataset curation.

- Silent Execution Risk: The primary danger lies in the agent silently executing malicious code. Standard output checks might miss the attack entirely, as the malicious action happens during the code execution step, possibly without leaving obvious traces in the final output or logs.

While larger models showed some increased resistance in the general BadAgent tests, the specific architecture and training paradigm of CodeAct agents makes them a particularly concerning target. As these powerful autonomous systems become more integrated into critical workflows (software development, cloud management), ensuring their security against such “silent sabotage” is paramount. Sourcing models and datasets from trusted origins and developing robust detection/defense mechanisms are crucial next steps.

Key Technologies

- Core Libraries: Python, PyTorch, Hugging Face (Transformers, Datasets, TRL),

unsloth(for QLoRA) - Models: Llama-2 (7B), Mistral (7B-v0.1), OPT (125m), BLOOM (560m, 1b7), DeepSeek (1.3b)

- Backdooring & Fine-tuning: QLoRA, Full Parameter Fine-tuning, Megatron-LM, Custom Poisoning Scripts

- Evaluation: vLLM (Inference), Standard Benchmarks (MMLU, HumanEval, GSM8K), Agent Benchmarks (MINT, MiniWoB++, ScienceWorld)

- Infrastructure: Linux, PACE ICE Cluster, Apptainer/Docker, Git